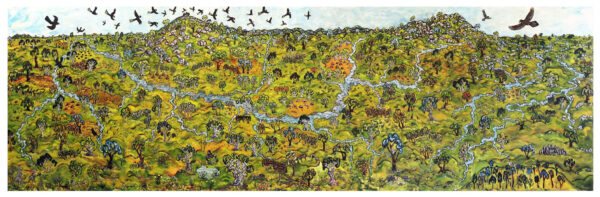

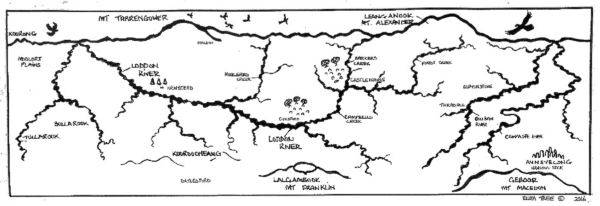

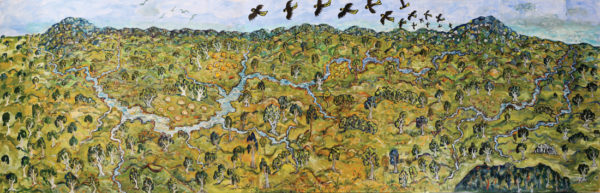

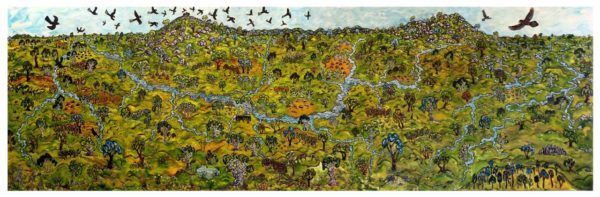

The Dawson Series

See The Dawson Series by Eliza Tree, 16 drawings based upon information drawn from James Dawson – Australian Aborigines: The Languages and Customs of several tribes of Aborigines in the Western District of Victoria, Australia. George Robertson Press 1881. All captions are from the book.

Who is James Dawson?

James Dawson was a Scottish ‘squatter’ in the Western district of Victoria in the 1850’s. He and his daughter Isabrella were some of the very few who were ‘sympathetic’ towards the local Tribe whose Country they ‘occupied’ They allowed the ‘rightful owners’ to continue to live on ‘their/his?’ land, and continue to live their cultural life and ways.

First published in 1881, Australian Aborigines holds unique insights into daily life and cultural material. Initially Dawson wrote shorty articles for local newspapers, and was scorned upon by other squatters for recognising their humanity, and defending the unjust treatment and attitudes towards ‘original owners of the land’

After deciding that his careful description of the tribes, languages, customs, and characteristics of the First Nations peoples of the western district of Victoria was too bulky for its originally intended publication in newspapers, he decided to publish this book. Essentially a field-inspired anthropological account of the local Aboriginal population, written before the emergence of anthropology as a formal discipline. Dawson’s book draws on his daughter’s ability to speak the local languages and attempts a balanced description of a culture he considered ill-used and under-appreciated by white settlers. Minute details about clothing, tools, settlement and beliefs combine to depict a complex society that possessed highly ritualised customs deserving of respect. Dawson also included an extensive vocabulary of words in three Indigenous languages that he hoped would facilitate further cross-cultural understanding. His work provides valuable source material for understand the complexity and utility of daily life in at the frontier of dispossession and land invasion.

The Dawson Series on the wall during Arts Open 22, March 2022

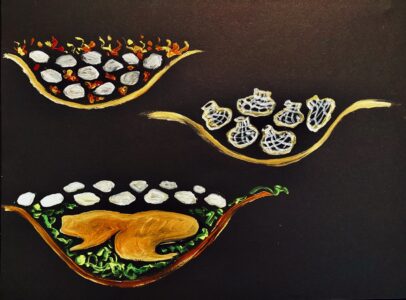

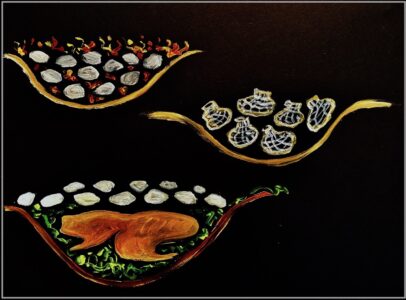

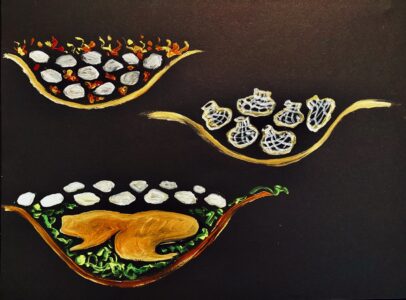

Eliza Tree, Woven grass mat with fishes, 2022

Eliza Tree, Fish trap & molluscs, 2022

‘Vast quantities of mollusca must have been consumed from very remote periods by the natives occupying the country adjoining the sea coast ; for opposite every reef of rocks affording shelter to shell fish, immense beds of shells of various sorts are to be seen in the sand-hills, in layers intermixed with pieces of charred wood, ashes, and stones having the marks of fire on them.’

Eliza Tree, Earth ovens, string bags & kangaroo, 2022

‘Ovens are made outside the dwellings by digging holes in the ground, plastering them with mud, and keeping a fire in them till quite hot, then withdrawing the embers and lining the holes with wet grass.

The flesh, fish, or roots are put into baskets, which are placed in the oven and covered with more wet grass, gravel, hot stones, and earth, and kept covered till they are cooked. This is done in the evening; and, when cooking is in common — which is generally the case when many families live together — each family comes next morning and removes its basket of food for breakfast.’

Eliza Tree, Earth Oven, 2022

‘Ovens on a greater scale, for cooking large animals, are formed and heated in the same way, with the addition of stones at the bottom of the oven ; and emus, wombats, turkeys, or forest kangaroos — sometimes unskinned and entire, and sometimes cut into pieces — are placed in them, and covered with leafy branches, wet grass, a sheet of bark, and embers on the top.’

Eliza Tree, Campsite and utensils, 2022

Eliza Tree, Food cooked on coals, 2022

‘Ordinary cooking, such as roasting opossums, small birds, and eels, is generally done on the embers of the domestic fire. When opossums are killed expressly for food, and not for the skin, the fur is plucked or singed off while the animal is still warm ; the entrails are pulled out through an opening in the skin, stripped of their contents, and eaten raw, and their place stuffed with herbs ; the body is then toasted and turned slowly before the fire without breaking the skin, and, if not immediately required for food, is set aside to cool.

By this method none of the juices of the meat escape; and what would otherwise be dry food is made savoury and nutritious. As the sinews, however, which are very strong, would render the meat tough, they are all pulled out previous to toasting, and are stretched and dried, and are kept for sewing rugs and lashing the handles of stone hatchets and butt pieces of spears.’

Eliza Tree, domestic furniture, 2022

‘Domestic Furniture: Every woman carries on her back, outside her rug, a basket made of a tough kind of rush, occasionally ornamented with stitches of various kinds. They also carry in the same way a bag formed of the tough inner bark of the acacia tree.

The capacity of these articles is from two to three gallons each, and in them are carried food, sticks and tinder for producing fire, gum for cement, shells, tools, charms, & etc.

The women also make a rougher kind of basket out of the common rush, which is used for cooking food in the ovens.’

Eliza Tree, Two types of grinding stone. 2022

‘There are two kinds of millstones, both formed of slabs of grey marble or grey slate, of an oval shape, eighteen inches long by twelve inches broad. One kind is hollowed out, like a shallow basin, to a depth of two inches ; the seed is put into it, and ground with a flat stone of the same material as the mortar.

The other kind is about the same size, but, instead of being basin-shaped, it is flat, and has two parallel hollows, each one foot long, five inches broad, and one inch deep, in which the seed is placed and reduced to flour by two flat stones, held one in each hand, and rubbed backwards and forwards.’

Eliza Tree, Domestic utensils, 2022

‘Domestic utensils are limited in number; and, as the art of boiling food is not understood, the natives have no pottery or materials capable of resisting fire. Their cookery is consequently confined chiefly to roasting on embers or baking in holes in the ground ; but as they consume great quantities of gum and manna dissolved together in hot water, a wooden vessel for that purpose is formed of the excrescence of a tree, which is hollowed out sufficiently large to contain a gallon or two of water. This vessel is placed near enough to the fire to dissolve the contents, but not to burn the wood. It is called ‘yuuruum,‘ and must be valuable, from the difficulty of procuring a suitable knob of wood, and from the great labour of digging it hollow with a chisel made of the thigh bone of a kangaroo.’

Eliza Tree, Water bags and trough, 2022

‘A small water-bag, called ‘paanuung’ is formed of the pouch of the kangaroo, which, when fresh, is stuffed with withered grass till it is dry. A strip of skin is fixed across its mouth for a handle.

For carrying water to a distance a bag called ‘kowapp’ is used. It is made of the skin of a male brush or wallaby kangaroo, cut off at the neck and stripped downwards from the body and legs, and made water-tight by ligatures. The neck forms the mouth of the bag. This vessel is carried on the shoulders by the forelegs.

For keeping a supply of water in dry weather, a vessel called ‘torrong’—

‘boat’ — is made of a sheet of bark stripped from the bend of a gum tree, about four or five feet long, one foot deep, and one wide, in the shape of a canoe. To prevent dogs drinking from it, it is supported several feet from the ground on forked posts sunk in the earth.’

Eliza Tree, Implements for Fire, 2022

Eliza Tree, Implements for Fire II, 2022

‘Implements for producing combustion are indispensable. These consist of the thigh bone of a kangaroo, ground to a long fine point, and a piece of the dry cane of the grass tree, about eighteen inches long. One end of the cane is bored out, and is stuffed with tinder, made by teasing out the dry bark of the messmate tree. The operator sits down and grasps the bone, point upwards, with his feet; he then places the hollow end of the cane, containing the bark, on the point of the bone, and, with both hands, presses downwards, and twirls the upright cane with great rapidity till the friction produces fire. Or, in the absence of the kangaroo bone, a piece of dry grass tree cane, having in its upper side a hole bored to the pith, is held flat on the ground with the feet, and the sharp point of a piece of soft wood is pressed into the hole, and twirled vertically between the palms of the hands till combustion takes place. Some dry stringy-bark fibre having been placed round the hole, the fire is communicated to it by blowing.’

Eliza Tree, eels, eggs, frogs & molluscs, 2022

‘The aborigines exercise a wise economy in killing animals. It is considered illegal and a waste of food to take the life of any edible creature for pleasure alone, a snake or an eagle excepted. Articles of food are abundant, and of great variety; for everything not actually poisonous or connected with superstitious beliefs is considered wholesome.

Of quadrupeds, they eat the several kinds of kangaroo, the wombat — which is excellent eating — the bear, wild dog, porcupine ant-eater, opossum, flying squirrel, bandicoot, dasyure, platypus, water rat, and many smaller animals.’

Eliza Tree, Roots and vegetables, 2022

‘Of roots and vegetables they have plenty. The muurang, which somewhat

resembles a small parsnip, with a flower like a buttercup, grows chiefly on the open plains. It is much esteemed on account of its sweetness, and is dug up by the women with the muurang pole. The roots are washed and put into a rush basket made on purpose, and placed in the oven in the evening to be ready for next morning’s breakfast. When several families live near each other and cook their roots together, sometimes the baskets form a pile three feet high.’

Eliza tree, Lizards, frogs, reptiles, 2022

‘The tortoise and its eggs are much sought after. Snakes are considered good food, but are not eaten if they have bitten themselves, as the natives believe that the poison, when taken into the stomach, is as deadly as when injected into the blood by a bite. Lizards and frogs of all sorts are cooked and eaten.

Of fish, the eel is the favourite; but, besides it, there are many varieties of fish in the lakes and rivers, which are eaten by the natives. One in particular, called the tuupuurn, is reckoned a very great delicacy. It is caught plentifully, with the aid of long baskets, in the mouths of rivers during its passage to and from the sea, of which migration the natives are well aware.’

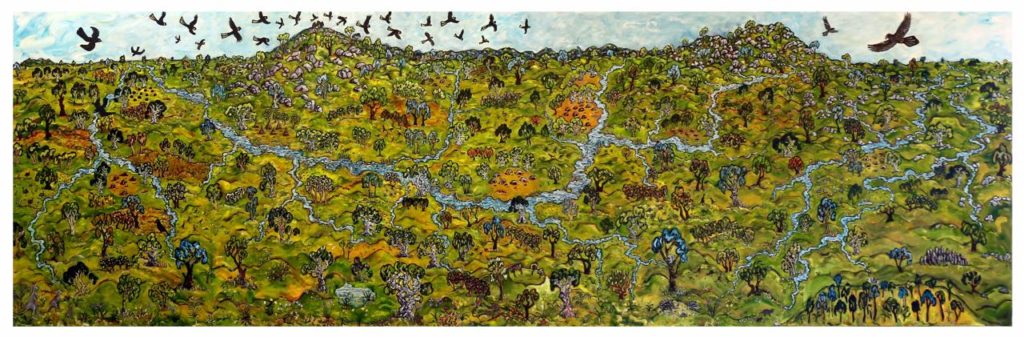

Eliza Tree, Habitation, 2022

‘Habitations — wuurns — are of various kinds, and are constructed to suit the seasons. The principal one is the permanent family dwelling, which is made of strong limbs of trees stuck up in dome-shape, high enough to allow a tall man to stand upright underneath them. Small limbs fill up the intermediate spaces, and these are covered with sheets of bark, thatch, sods, and earth till the roof and sides are proof against wind and rain. The doorway is low, and generally faces the morning sun or a sheltering rock.

[Source: James Dawson Australian Aborigines, George Robertson Press, 1881]

The family wuurn is sufficiently large to accommodate a dozen or more persons; and when the family is grown up the wuurn is partitioned off into apartments, each facing the fire in the centre, One of these is appropriated to the parents and children, one to the young unmarried women and widows, and one to the bachelors and widowers.

When it is necessary to abandon them for a season in search of variety of food, or for visiting neighbouring families and tribes, the doorway is closed with sheets of bark or bushes, and, for the information of visitors, a crooked stick is placed above it pointing in the direction which the family intends to go. They then depart, with the remark, ‘Muurtee bunna meen,‘ — ‘close the door and pull away.’